Frank Wouters

Chairman MENA Hydrogen Alliance

Share

A Small Molecule with a Big Potential in MENA

Climate change is finally receiving the attention it deserves. According to IPSOS, two thirds of the global population is concerned about the consequences of global warming and expects more action from public and private leadership. The Sixth Assessment Report of the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), released in August 2021, was a wake-up call: the window of opportunity to avoid climate chaos is closing fast.

The energy sector – one of the largest sectors of the global economy – has traditionally been a major source of greenhouse gas emissions. However, in recent years, clean energy solutions have been developed that are now quickly becoming the bedrock of positive climate action.

The energy sector is integral to development and our modern way of life. Low carbon energy technologies include renewable energies, storage solutions, carbon capture and storage (CCS) and hydrogen, and have proven to be cost-effective alternatives to unabated combustion of fossil fuels.

With increasing deployment, economies of scale and ever higher efficiencies, modern renewable electricity is now on average cheaper than conventional fossil power and quickly replacing coal, natural gas, and oil power stations all over the world.

Hydrogen

Low carbon hydrogen will play a crucial role in our decarbonized future economy, as shown in many recent scenarios. In a system soon dominated by variable renewables such as solar and wind, hydrogen links electricity with industrial heat, materials such as steel and fertilizer, space heating, and transport fuels. Furthermore, hydrogen can be seasonally stored and transported cost-effectively over long distances, to a large extent using existing natural gas infrastructure.

Green hydrogen in combination with green electricity has the potential to entirely replace hydrocarbons, although blue hydrogen, made from natural gas with CCS, will help meet hydrogen demand in the short to medium term. More than half of all hydrogen initiatives are in Europe and predictions for hydrogen’s share in the EU’s final energy demand by 2050 range from 24% to 50%. An estimated 50% of that will be imported.

With all its promise, hydrogen still faces many barriers before it can become a globally accepted energy commodity.

Green hydrogen made from renewable electricity and water is currently still more expensive than conventional hydrogen but is expected to become cost-competitive within a decade. The 2020s are described as the “hydrogen’s decade” by the likes of HSBC and Wood Mackenzie, building on the IEA’s landmark 2019 report “The Future of Hydrogen” calling for international action to tap into hydrogen’s vast potential.

With all its promise, hydrogen still faces many barriers before it can become a globally accepted energy commodity. Many aspects of the hydrogen ecosystem require R&D effort, there is a lack of internationally recognized standards, and it is still unclear what financial mechanisms are most suitable to cover the short to medium term cost gap.

Hydrogen in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA)

Many countries and regions that will have a high hydrogen demand, such as the EU and Japan, do not have sufficient solar and wind potential to produce the green hydrogen they need. This gives a competitive advantage to countries with abundant resources such as the MENA region, which is situated in the world’s sun belt. In addition to the solar and wind resources, Gulf countries can also build on the hydrocarbon infrastructure and expertise and tap into low-cost capital. These endowments can become a crucial basis to compete as future hydrogen exporters. Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries can hence retain the basic business model of the oil era, cheap production of a universally used fuel. Also, the ability to start blue hydrogen production immediately using abundant low-cost hydrocarbons gives the GCC countries an additional competitive edge. But equally, countries that are currently net energy importers such as Morocco and Jordan, green hydrogen made from indigenous renewable energy promises a more secure and affordable energy future.

Contrary to now, Gulf countries will have to learn to compete with a broader set of countries and regions, including North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, Australia, Chile and India. But many of these countries, especially in Africa, are lacking the investment capital and business environment to rapidly engage in hydrogen production and export, providing a competitive edge for Gulf countries with low cost of capital.

A recent study carried out by Dii Desert Energy and Roland Berger found that a GCC hydrogen economy could create 1 million new jobs and generate $200bn in annual revenue by 2050.

Hydrogen in the GCC

Three of the six Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries have embarked on ambitious hydrogen journeys: Oman, Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

Oman

In 2021, Oman established a national hydrogen alliance, known as Hy-Fly, led by the Ministry of Energy and Minerals, will initially have 13 members, which includes government agencies, oil and gas operators, educational and research institutions and ports that will work together to support and facilitate the production, transport, domestic use and export of clean hydrogen.

Oman has access to the Arabian Sea and is blessed with strong winds and abundant sunshine, a combination that ensures high load factors for water electrolyzers. Several initiatives have been launched, including:

- Duqm. The Indian company ACME is developing a large-scale facility to produce green hydrogen and green ammonia at the Duqm Free Zone. The plant with an investment of $3.5 billion will be an integrated facility using 3 GWp of solar and 0.5 GW of wind energy to produce 2,400 tonnes per day of green ammonia with an annual production of about 0.9 million tonnes. The green ammonia will be exported to demand centres like Europe and Asia.

- Green Energy Oman. A consortium consisting of the state-owned oil and gas company OQ, the Hong Kong-based renewable hydrogen developer InterContinental Energy and the Kuwait-based energy investor Enertech is planning to build one of the largest green hydrogen plants in the world in a move to make the oil-producing nation a leader in renewable energy technology. Construction of the $30bn project is scheduled to start in Al Wusta governorate on the Arabian Sea in 2028. It will be built in stages, with the aim to be at full capacity by 2038, powered by 25 GW of wind and solar energy. The project will produce 1.8 million tons per annum of green hydrogen and up to 10 million tons per annum of green ammonia to make Oman a world leader in truly zero carbon fuels.

Saudi Arabia

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is driving a dual track with Saudi Aramco as the champion of blue hydrogen, and NEOM, a new city in the north-west of the kingdom championing green hydrogen.

NEOM (the word is an original mix of ‘new’ in English and ‘yawm’ (‘day’ in Arabic) means a ‘new day’. It is rare when countries build big cities from scratch. Often, such projects are politically motivated, as was the case in Kazakhstan, Brazil and Nigeria. Astana – renamed to Nur-Sultan and Kazakhstan’s capital – was meant to be further away from the Chinese border; Abuja, Nigeria’s capital, was in the center of the country to be closer to the Northern Nigerian States; and Brasilia, Oscar Niemeyer’s vision of a future city with stunning architecture, was also located in the center of Brazil to be closer to a larger part of Brazil’s population. Abuja, Nur-Sultan and Brasilia are all located in a much more central location than the capital cities they succeeded.

backer-sha-ZC1go68bTic-unsplash_Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Source: Backer Sha / Unsplash

NEOM is part of Saudi’s Vision 2030 and a planned city in the Tabuk Province of north-western Saudi Arabia. NEOM is different in several ways. Firstly, it is not centrally-located nor intended to replace Riyadh as Saudi Arabia’s capital. Secondly, NEOM’s sheer size, at 26,000 square kilometers (the size of Belgium), and its unique constitution-like legal framework, make it a hybrid between a city and a country. NEOM is pursuing a zero-carbon philosophy for its energy system, based on solar and wind. NEOM’s location is an important factor in that respect. Not only are the solar and wind resources of very high quality, but they are also very complementary. The wind is predominantly of thermal origin over the Red Sea and picks up every afternoon. So, when the sun sets, the wind starts picking up and a combination of the two provides for an exceptionally high annual load factor of more than 70%.

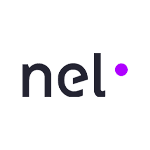

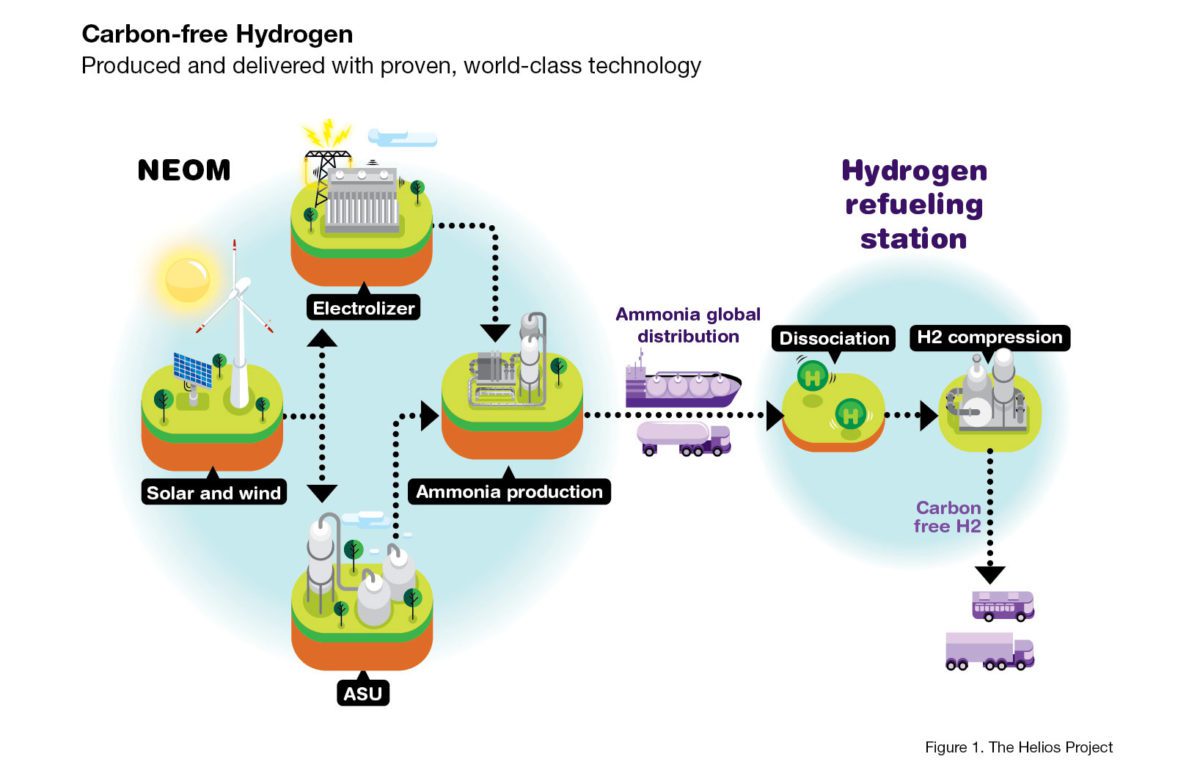

In July 2020, a consortium of NEOM, Air Products and ACWA Power announced the launch of the HELIOS project. HELIOS will be equally owned by the three partners, will integrate 4GW of renewable power from solar, wind and storage, the production of 650 ton per day of hydrogen by electrolysis, the production of nitrogen by air separation and the production of 1.2 million ton annually of green ammonia. The project is scheduled to be onstream in 2025. Air Products will guarantee the offtake of ammonia and distribute it to global markets, aiming to dissociate ammonia at hydrogen refueling stations (Figure 1).

Thyssenkrupp has been selected as provider of the electrolysers, Air Products will supply the air separation unit and Haldor Topsoe will supply the ammonia synthesis unit. ACWA Power is responsible for the development of the renewable energy projects. Air Products is responsible for the overall engineering, procurement and construction of the project.

A 1.2 million ton/a ammonia project is large, but not unusual, with most modern ammonia projects in the million-ton range. The Gulf Coast Ammonia project in Texas, under construction as of 2021, has a similar capacity of 1.3 million ton anhydrous ammonia per year. It is not a coincidence that Air Products is involved in that project, supplying hydrogen from a steam methane reforming unit and nitrogen from an air separation unit. It is fair to assume that a large part of the knowledge gained in the Gulf Coast Ammonia project informed the HELIOS project. But the HELIOS project itself will significantly contribute to the development of the global hydrogen economy. The size of the investment that Air Products is making, both in NEOM and in its sales and distribution network to deliver the NEOM product, is impressive. Beyond the $5 billion plant cost, AP will invest an additional $2 billion in “distribution to end customers.” Building this plant will have a significant impact on the cost of electrolyzers and on the cost of ammonia crackers. The cost of initial infrastructure to deliver this volume of ammonia might be significant, but those volumes can later be expanded at far lower incremental delivery cost. Going further, the second and third big green ammonia plants will be cheaper; the second and third hundredth plants will have economics that we’ve yet to quantify.

UAE

Grey hydrogen from fossil fuels is already widely used in the UAE but is currently not a widely traded commodity. however, the UAE is developing ambitious plans to deploy hydrogen not only as a key pillar of decarbonization but also creating new export markets. In 2020, Abu Dhabi’s Supreme Petroleum Council instructed the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC) to become a “hydrogen leader”. The formation this year of the Abu Dhabi Hydrogen Alliance between ADNOC, Mubadala, ADQ, and the Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure was a further important step towards building a UAE hydrogen ecosystem. Several initiatives are currently being developed:

kizad-new_pixelated

Master plan for the KIZAD Industrial Zone where the Helios project will be located. Source: KIZAD

HELIOS. Khalifa Industrial Zone Abu Dhabi (KIZAD) will develop a green ammonia plant, with up to $1 billion invested over the coming years. Helios Industry, a private special projects company, will develop the plant in two phases alongside local and international partners. The project, which will be powered by an 800 MWp solar power plant within KIZAD, is expected to produce 200,000 tonnes of green ammonia from 40,000 tonnes of green hydrogen.

ADNOC. Abu Dhabi National Oil Company announced the development of a large blue ammonia project at its downstream centre in Ruwais as it looks to expand the UAE’s hydrogen economy. It will have a capacity of 1,000 kilotonnes a year. The blue ammonia facility is currently in the design phase and will be built within the Ta’ziz industrial complex at Ruwais. Ta’ziz is a $5bn joint venture between ADNOC and ADQ.

TAQA. TAQA, one of the largest listed integrated utilities in the region, and Abu Dhabi Ports are developing an industrial scale green hydrogen to ammonia export project in Abu Dhabi. The companies will work together on a green ammonia export facility to be based in Khalifa Industrial Zone Abu Dhabi (KIZAD). The new plant would be fuelled by hydrogen produced by an electrolyzer facility paired with a 2 GWp solar photovoltaic (PV) power plant. The green hydrogen would be turned into liquid ammonia to supply ships converted to use ammonia as a bunker fuel and for export from Abu Dhabi Ports via specialized gas carriers. The project will also feature a storage facility at Khalifa Port, opening the opportunity for it to become a hub for exporting green ammonia to international markets including Europe and the East Asia.

Hydrogen in North Africa

A number of non-GCC MENA countries have also started exploring green hydrogen opportunities, including Morocco, Egypt and Jordan.

Morocco

The Southern Mediterranean countries can currently be divided in net energy importing and net energy exporting countries. Libya and Algeria have built their economies on the back of their substantial oil and gas reserves, whilst Morocco has always had to import fossil fuels.

Morocco has embarked on an ambitious renewable energy program with a target of 52% of renewable electricity by 2030. The state-owned entity MASEN plays a pivotal role. MASEN pre-develops renewable energy sites, carries through the procurement process, acts as the government entity borrowing concessional finance from development finance institutions and commercial lenders, and co-invests on behalf of the government. In Ouarzazate, a beautiful city south of Morocco’s High Atlas Mountains, known as a gateway to the Sahara Desert and known from “Game of Thrones”, Morocco built the Noor solar complex, consisting of CSP and PV projects, totaling 582 MW at peak. The scale of these projects and Morocco’s clever financial engineering, have brought down the cost of CSP, which is now competitive with conventional power.

The energy ties between Europe and North Africa are very strong today; 13% of the gas and 10% of the oil consumed in Europe comes from North Africa, and over 60% of North Africa’s oil and gas exports are sent to Europe.

The electricity grid infrastructure in North Africa is not well developed, requiring major reinforcements and expansion in the coming decades, especially to transport electricity from the good solar and wind resource areas to the demand centers in the cities and rural areas.

Today, there is only one electricity grid connection between Europe and North Africa, the 700 MW grid interconnector between Spain and Morocco. However, there is a gas transport infrastructure available between North Africa and Europe, transporting gas from Algeria and Libya to Europe via Italy and Spain. The gas transport volume through these pipelines is over 63.5 bcm per year, which equals a capacity of more than 60 GW.

In a first phase, between 2030-2035, the natural gas infrastructure could be used to transport hydrogen from North Africa to Europe. Initially, a substantial hydrogen volume can be produced by converting natural gas to hydrogen, whereby the CO2 is stored (blue hydrogen). Over the years however, with declining cost of renewable electricity and electrolyzers, more and more green hydrogen from solar and wind electricity can be fed into these pipelines. Eventually, purpose-built hydrogen pipelines would connect Moroccan production sites with the European hydrogen backbone.

48962353822_9ff323e639_o_Ouarzazate Solar Power Station_RichardAllaway_Flckr_cc

Ouarzazate Solar Power Station. Source: Richard Allaway / Flckr

OCP. One of the largest phosphate mining companies in the world is Morocco’s OCP. The phosphate mined in Morocco is combined with imported ammonia to produce fertilizer. OCP currently import 1-2 million tons of grey ammonia but has been studying local production of green ammonia. Given Morocco’s excellent solar and wind resource, ability to attract concessional finance and execute well-managed projects, should enable them to produce green ammonia cost competitively if one factors in a price on carbon (currently there is no carbon market in Morocco, but that is not likely to remain so).

HEVO. In July 2021, trading firm Vitol signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) to manage offtake from the Hevo Ammonia Morocco project, which is being developed by Ireland-based green hydrogen technology company Fusion Fuel and Middle East construction company Consolidated Contractors. The location of the facility has not yet been finalised, but it is expected to be in the vicinity of Jorf Lasfar, Essaouira or Agadir. The project would be Morocco’s largest green ammonia and green hydrogen project, with an estimated total investment value of around $850 million. Development of the first phase is expected to begin in 2022 following the completion of a feasibility study. When fully commissioned, the project is expected to produce 183,000 t/yr of green ammonia. Fusion Fuel expects to supply the technology to produce the 31,000 t/yr of green hydrogen that the project will need.

Egypt

The production of hydrogen by water electrolysis using hydropower has a long tradition in Egypt. The KIMA Company in Aswan started producing green hydrogen in 1960, and only changed to natural gas recently. In addition to hydropower, Egypt is also blessed with excellent solar and wind, making it a good location for green hydrogen production.

German projects. The Egyptian government this year signed two MoU’s with Germany’s Siemens and ThyssenKrupp. In January 2021, the Egyptian Minister of Electricity and Renewable Energy, Mohamed Shaker, signed an MoU with Siemens CEO Joe Käser to study the implementation of a pilot project for the production of green hydrogen in Egypt, as a first step towards potential export. In May 2021, Egyptian Prime Minister Mustafa Madbouli held a meeting with Oliver Tietze, the CEO of Thyssenkrupp Industrial Solutions, to discuss establishing a factory for green ammonia and green hydrogen production in Egypt, with the aim to to export the green ammonia from Egypt to Germany.

Jordan

Jordan is a net energy importer and has been receiving natural gas from Egypt through the Arab Gas Pipeline, which has a capacity of 10bcm/a. However, from 2011 onwards, the supply of gas has been seriously reduced due to a shortage of gas in Egypt, and at least 26 attacks on the pipeline in the period between 2011 and 2014. This made Jordan pivot towards indigenous solar and wind power, through a smart system of consecutive auctions, leading to competitive power rates. Like Egypt and Morocco, Jordan has ample land and an excellent solar and wind resource. The share of electricity from renewables in Jordan grew from 0.7% in 2014 to over 13% in 2019, making Jordan a regional front-runner in renewable energy.

The energy ties between Europe and North Africa are very strong today; 13% of the gas and 10% of the oil consumed in Europe comes from North Africa, and over 60% of North Africa’s oil and gas exports are sent to Europe.

Dii Desert Energy carried out a study assessing the potential for exporting green hydrogen from MENA to Europe, and assessed the potential in Jordan. It should come as no surprise that the potential is vast, given the strategic location, including suitable infrastructures, such as an existing gas pipeline to Egypt, a natural gas link to Israel, an LNG terminal in Aqaba and of course excellent solar and wind resources, also in the south of the country where desalinated seawater would be close. In addition, Jordan has a sizable chemical business, largely focused on potassium and bromine industries. They could act as local off-taker for green molecules, and create value added downstream industries. With the high prices for energy, trucks and buses might also be powered by green hydrogen in the future, and a large refinery south of Amman could use green hydrogen. The ambitious NEOM project, just 200 km south of Aqaba, could be a partner, rather than a competitor for production of green hydrogen or Ammonia, to create synergies locally and for export. Undoubtedly, Jordan would have all ingredients to produce low-cost green hydrogen, with the possibility to export internationally via the Aqaba port. Many jobs have been created in the solar and wind sector, and Jordan could build on this to develop a green hydrogen economy.

FMG. A delegation from Andrew Forrest’s Fortescue Metals Group met with the Jordanian government in April 2021. They discussed potential opportunities of exploring green hydrogen and ammonia with the Jordanian Minister of Planning and International Cooperation Nasser Al-Sharida, potentially for export purposes.

Hydrogen Action

We can see growing momentum in countries of the Middle East and North Africa towards green hydrogen developments. Many such initiatives are still in the earlier stages, but their number is growing. At the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow (November 2021), governments, including in MENA, must achieve consensus on decisive climate action. Clean energy and hydrogen will be part of the solution to the climate crisis. Immediately after COP26, ADIPEC, the largest annual global gathering of energy executives will take place in Abu Dhabi. ADIPEC will have a full sub-section of sessions dedicated to hydrogen, in which the energy sector can discuss the climate conference’s key recommendations.

If the 2020s are indeed to be hydrogen’s decade, several elements appear critical to its success:

- Integration in economies’ post-COVID recovery programs. The momentum unleashed by governments in the wake of the pandemic must be channeled in the right direction, as expressed in the often-used phrase “build back better”. The global tragedy could be used to start a transformation towards a cleaner, just, and more inclusive societal fabric. Although much of the recovery money has been channeled to putting the status quo back on its feet, there is still some opportunity left to build back better.

- A conducive policy framework to incentivize the necessary investments. The private sector is capable to innovate and provide the capital for the energy transformation. Governments should provide the policy frameworks for the private sector to do so at the required speed and in the right direction, for example by setting standards, providing carrots (subsidies) and sticks (quotas), devise international treaties and regulate markets.

- Rapid scaling-up of technologies to reduce the cost gap. Support for innovation and research, development and demonstration will lead to accelerated deployment of low-carbon hydrogen.

There is great momentum for green hydrogen all over the world including in the Middle East and North Africa. It’s time for the energy sector to come together around this clean fuel’s immense potential.